Posted On:

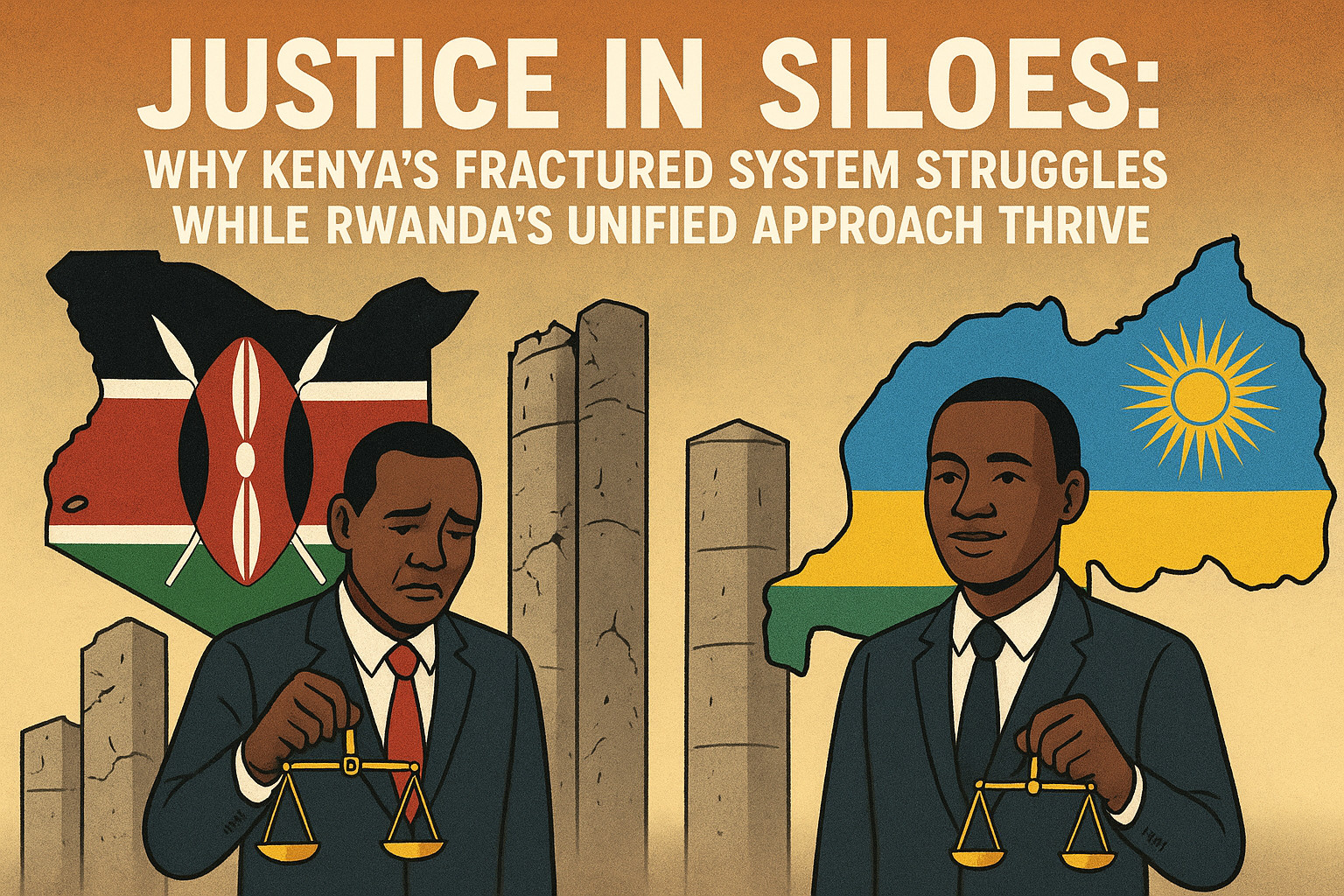

Kenya Struggles While Rwanda’s Unified Justice Thrives

A victim of a crime in Kenya will report to the police, then to the Director Public Prosecutions (different system). It then proceeds to court (where the Judiciary uses its own, isolated e-filing system). Finally, if convicted, the offender is sent to the Prisons service (which has yet another database). At every step, data must be manually re-entered, files get lost, and delays are inevitable.

This is the reality of Kenya's justice sector.

Now, imagine the same scenario in Kigali. A single case file number generated at the police station seamlessly travels through the entire justice chain—prosecution, courts, corrections—on one unified digital platform. All actors see the same real-time information. This is not a futuristic dream; it is Rwanda’s present-day reality.

The difference? Coordination.

The Kenyan Conundrum: A House Divided

Kenya’s justice sector is architecturally flawed from the outset. As noted, all key justice actors—the National Police Service, Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP), Witness Protection Agency, and the Department of Corrections—fall under the Executive arm of government. The Judiciary stands alone as an independent arm.

This structure creates a fundamental power imbalance and a crisis of coordination. The National Council on the Administration of Justice (NCAJ), chaired by the Chief Justice, was established to bridge this gap. However, as its own 2020-2024 Strategic Plan admits, the NCAJ struggles with "inadequate compliance with directives by member agencies" and "weak monitoring and evaluation mechanisms." Essentially, it lacks the authority to compel action from Executive bodies.

This dysfunction manifests technologically in the proliferation of disconnected Case Management Systems (CMS):

Judiciary: Integrated Case Management System (ICMS)

Office of the DPP: Case Management Platform (CMP)

National Police Service: Various incident reporting systems (e.g., Occurrence Book modules)

Reports like the UNDP’s Justice Needs & Satisfaction Survey consistently highlight the consequences: case backlogs, lost files, and a frustrating experience for citizens. The system is not just slow; it is a collection of isolated siloes that rarely communicate effectively.

The Rwandan Blueprint: A Symphony of Coordination

Rwanda took a radically different approach. Following the 1994 genocide, rebuilding a cohesive, efficient, and trustworthy justice system was a national priority. They established an Integrated Justice Sector (IJS) model, where all agencies operate under a single, shared policy and vision, driven from the top.

Coordination is mandated and enforced. All justice institutions are aligned towards common goals outlined in their national strategic plans, such as the Justice Sector Strategic Plan (JSSP).

The crown jewel of this integration is Ijuridium, a single, unified case management system. From the moment a case is initiated by the police, it is tracked on this one platform. Prosecutors, judges, and prison officials all interact with the same digital case file. This eliminates redundancy, drastically reduces delays, and creates unparalleled transparency and accountability.

World Bank and East African Community reports on Rwanda’s governance consistently praise this "whole-of-government" approach. It is a testament to how a clear vision and strong political will can create a seamless justice infrastructure.

Head-to-Head: A System Comparison

FeatureKenyaRwanda

Governance ModelFragmented. Judiciary independent; other actors in the Executive.Integrated Justice Sector (IJS). All agencies work under a unified command structure.

Coordination BodyNational Council on the Administration of Justice (NCAJ) - Weak mandate.Sector-wide coordination - Strong, enforced mandate.

Case ManagementMultiple, siloed systems (ICMS, CMP, etc.) that may not communicate.One Unified System (Ijuridium) for all actors from police to prisons.

Data FlowManual data transfer between systems, leading to errors and delays.Seamless, automated real-time data sharing across the entire chain.

Citizen ExperienceOften frustrating, repetitive, and slow. Requires navigating multiple systems.Streamlined, more predictable, and transparent.

Key ChallengeLack of inter-agency cooperation and political will to cede control of data.Maintaining the system and ensuring continuous capacity building.

Lessons for Kenya: The Path to a Unified Justice System

Kenya does not need to copy Rwanda, but it must learn from its principles. The solution is not just to build another software platform but to fix the governance problem first.

Empower the NCAJ: The NCAJ must be strengthened, possibly through legislation, to give its directives legal force. Compliance from member agencies cannot be optional. It needs a secretariat with real authority.

Prioritize Interoperability: As an immediate step, the government must mandate and fund the development of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to connect the existing ICMS, CMP, and police systems. This is a technical fix that can yield quick wins while a long-term solution is developed.

Adopt a "One-Case" Philosophy: The goal should be a single digital case file that belongs to the citizen, not to a specific institution. This change in mindset is crucial.

Secure Top-Level Political Buy-In: The President and the Chief Justice must jointly champion this initiative. Without high-level political will to break down institutional barriers, any technical solution will fail.

Learn from Ijuridium: Kenya should study the architecture and implementation challenges of Rwanda’s system to avoid pitfalls and accelerate its own development.

Conclusion: A Call for Political Will, Not Just Technology

Rwanda’s success with a unified case management system is a symptom of a deeper achievement: a coordinated, purpose-driven justice sector. Kenya’s struggle with multiple systems is a symptom of its fractured governance.

The lesson for Kenya is clear: technology alone cannot solve a governance problem. Before investing in a new national CMS, Kenya must first invest in building the political consensus and institutional frameworks that will allow it to succeed. The blueprint for a more just, efficient, and trustworthy system exists. What is needed now is the courage to break down the siloes and build it.

What do you think? Should Kenya prioritize a unified justice system? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Comments